When an internal combustion engine is disassembled for a rebuild or a major repair, the focus often shifts immediately to the pistons, rings, and bearings. However, the foundation of a successful engine build lies in the integrity of its mating surfaces. Specifically, the relationship between the engine block and the cylinder head is the most critical seal in the entire vehicle.

Engine block resurfacing, often called “decking,” is the precision machining process used to ensure the block’s top surface is perfectly flat and possesses the correct texture to hold a seal under extreme pressure. As modern engines move toward higher compression ratios and more sophisticated gasket materials, the margin for error in resurfacing has virtually disappeared.

In this comprehensive guide, we will explore why resurfacing is vital, the technical science behind surface finishes, and how to determine if your engine block can be saved or if a higher-quality replacement is the more secure path for your build.

The engine block deck is the “floor” upon which the cylinder head sits, with the head gasket acting as the critical barrier between them. This area must contain three distinct elements: high-pressure combustion gases, circulating coolant, and pressurized engine oil.

Engine blocks are subjected to thousands of heat cycles. Over time, the constant expansion and contraction can cause the metal to “move.” In aluminum blocks, this often manifests as a slight bow or twist. In cast iron blocks, while more stable, localized overheating can cause the deck to distort near the exhaust valves or between the middle cylinders. If the surface is not perfectly true, the head gasket cannot apply even pressure, leading to “blow-by” or coolant mixing with oil.

Modern cooling systems are efficient, but if the coolant is not changed regularly, it can become acidic. This leads to electrolysis, which literally eats away the metal around the coolant passages of the block. This “pitting” creates channels through which fluids can escape. Resurfacing removes this damaged layer of metal, exposing fresh, flat material that a new gasket can bond with.

The automotive industry has largely transitioned from soft, composite head gaskets to Multi-Layer Steel (MLS) gaskets. While MLS gaskets offer superior durability and heat resistance, they are far less “forgiving” than their predecessors. A composite gasket could squash into minor imperfections; an MLS gasket requires a surface that is nearly as smooth as glass to function correctly.

In the world of engine block resurfacing, “flatness” is only half of the story. The other half is the surface finish, measured in Roughness Average (RA). This is where many DIY projects and budget machine shops fail.

If the RA is too high for an MLS gasket, the steel layers cannot conform to the deep grooves left by the machining tool. Combustion pressure will eventually find its way through these microscopic valleys. Conversely, if a surface is too smooth for a composite gasket, the gasket may “walk” or move under the pressure of the cylinder head, eventually leading to a failure. A professional resurfacing job uses a tool called a profilometer to verify that the RA meets the gasket manufacturer’s exact specifications.

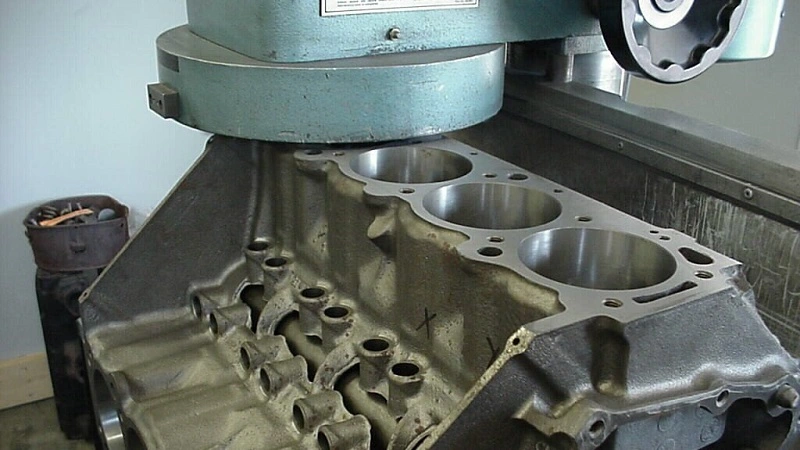

Resurfacing an engine block is not a task that can be performed with hand tools or sandpaper. It requires massive, rigid industrial machinery capable of removing metal in increments as small as 0.0005 inches.

A block cannot be machined if it is dirty. Professional facilities start by “hot tanking” or using ultrasonic cleaners to remove all oil, carbon, and scale. Once clean, the block is inspected for cracks using magnetic particle inspection (Magnaflux) for iron or dye penetrants for aluminum.

Before the first cut is made, the technician uses a precision straightedge and feeler gauges to map the warpage. They also measure the current deck height—the distance from the crankshaft centerline to the top of the block. This measurement is crucial because it determines how much metal can safely be removed without causing the pistons to hit the cylinder head or excessively raising the compression ratio.

The block is mounted in a surfacing machine, often a CNC mill or a dedicated rotary surfacer. The most important part of the setup is ensuring the block is indexed off the crankshaft main bores. This ensures that the new surface is perfectly parallel to the crank. If a shop simply “shaves” the top based on the old surface, the deck may end up slanted, leading to uneven engine performance.

When you decide to resurface an engine block, there are several “downstream” effects that must be managed to ensure the engine runs correctly once reassembled.

As you remove metal from the block, you reduce the volume of the combustion chamber. This increases the compression ratio. While a slight increase can improve power, too much can lead to engine “knock” or “pinging,” especially with lower-octane fuels. In some cases, a thicker “head gasket spacer” or a custom-thickness MLS gasket must be used to compensate for the material removed during resurfacing.

After a block is machined, the edges of the cylinder bores and bolt holes are often as sharp as a razor. These sharp edges can become “hot spots” that glow red-hot during combustion, causing pre-ignition. A professional machinist will always go back and “chamfer” or break these sharp edges to ensure a safe and smooth assembly.

One of the most common mistakes is ignoring the timing cover. On many modern engines, the front timing cover is flush with the top of the block. If the block is resurfaced without the timing cover attached, the cover will be “taller” than the block when you go to reassemble the engine. This creates a step that no head gasket in the world can seal. Always ensure that any components that share the deck surface are machined at the same time as the block.

Another mistake is failing to clean the bolt holes. If metal shavings or old oil are left in the head bolt holes, they can cause “hydraulic lock” when the bolts are tightened. This can lead to inaccurate torque readings or, worse, cracking the engine block casting.

While engine block resurfacing is a common way to restore a used engine, it is not always the most efficient or safest path. If a block is severely warped or the deck is deeply pitted, removing enough metal to fix it can leave the surface too thin to support high-pressure combustion.

In these cases, the variables and risks of machining often outweigh the costs. Choosing a brand-new, factory-spec cylinder head or block ensures you have a “zero-hour” component with perfect structural integrity. A new part eliminates concerns about timing chain slack or altered compression ratios, providing the most reliable foundation possible for your engine’s future performance.